All at Sea at Fifteen

The time when my Mum told school I wouldn't be there for two months so I could go sailing - at 15 years old, on a boat built in the 1850s, with a group of people we didn't know.

UPDATE February 2026

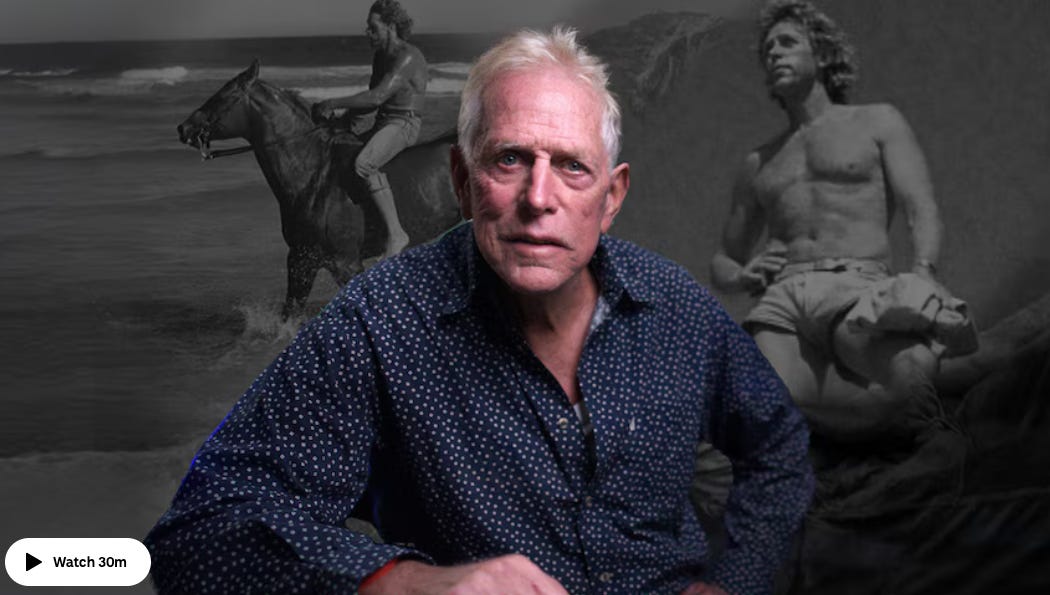

The ABC program, Australian Story, this week was about Alby Mangels, the documentary maker from World Safari I mentioned in this article. The program includes footage he filmed on the Klaraborg.

Hey Mum and Dad, can I please take a term off school and go sailing? With a bunch of people you’ve never met. On a boat built in the 1850s? That requires constant maintenance to plug leaks? Down the remote west coast of Western Australia?

We all have sliding-door moments—in my case, even before I was born. In the 1950s, my parents married in England and moved to West Africa. This was a decision beyond comprehension for many. However, if you are conscious of history, England was still a disaster zone in the early 1950s following the devastation of the Second World War. Some foods were still rationed, and the economy was in pieces after needing to be focused purely on wartime production.

Mum and Dad went to West Africa in search of a new frontier, away from the trauma of the war. This sliding door means I was born in Ghana in the late 1960s - still a topic of conversation at the immigration desk of airports when the border people look at my white face and the place of birth in my passport.

The second big sliding door was my family's move from the comfortable suburbia of Surrey, south of London, to another new frontier, Darwin, in Australia, a year after the city was devastated by Cyclone Tracey.

I had a sliding door moment in 1981. I was in Year 10 at St John's Catholic College in Darwin. We saw in the newspaper an article about a large old sailing boat arriving in the harbour and offering tours. My siblings and I were keen sailors, mostly racing small catamarans on the harbour, so it seemed natural we should ask Mum if we could go and see this boat.

The Klaraborg was a marvel. It was a historical Baltic trading ship, originally constructed in the 1850s in Vanesborg, Sweden. It was a gaff-rigged ketch built to transport zinc ore around Swedish lakes and waters.

The ship was sturdily constructed with a double-planked pine hull on seven-inch-thick oak frames. She had an 80-foot-long pine-planked deck with a 36-foot-long jib-boom and bowsprit, making its overall length 116 feet. The beam was 22.5 feet, and its draught was 8.5 feet. (If you are a sailor, this will all make sense!).

The Klaraborg was reclaimed from "the salvage heap of time" when it was 106 years old. A group of young Swedish men rebuilt and refitted her and set sail from Göteborg, Sweden, in 1967. For the next fifteen years, the ship sailed around the world, visiting numerous exotic ports from Sydney to Hong Kong, Rio to Tahiti, and San Francisco to Cape Town.

Along the way she played a key part in a popular documentary film World Safari starring an adventurer named Alby Mangels. You can find grainy footage of the film, with the Klaraborg, on Youtube.

So this was the remarkable boat we toured in Darwin Harbour. I was entranced by the whole thing…..including a sign advertising for crew. For a weekly payment, which went towards board, food and boat upkeep, you could join the Klaraborg crew for as long as you wanted. Cue a sliding door moment, because Mum and Dad decided, hey, why not! Mum wrote a letter to the principal of my school informing him that David wouldn’t be at school the next term, and I embarked on an eight-week adventure as part of the crew sailing the Klaraborg from Darwin until I left the boat in Fremantle.

My time on the Klaraborg was a world of firsts for this closeted, unworldly (mostly) private school-educated teenager:

I slept on deck for the first couple of weeks because there weren’t any spare bunks below. It was not a huge impost; warm weather, a breeze. It just could be challenging to stay asleep when other crew on watch were on deck, needing to adjust the sails or perform some other maintenance task.

Seeing a large shark caught on a line, necessitating the skipper pulling out a rifle (not sure completely legally owned) and shooting the shark dead, then helping to cut out the jaws to clean and mount in the cabins.

Sitting outside pubs in remote towns like Exmouth while the adult crew drank, because I was underage.

Learning how to sail something ten times the size of my little catamaran, with everything completely manual, hauling sails up and down with blocks and tackle in the middle of the night, no powered winches or other mod cons.

Helming during my watch, maybe midnight to 4am, just moonlight, a strong swell, a dimly lit compass whilst watching the wind, the sails and holding course.

Watching the skipper navigate us over the open ocean, with no autopilot or electronic chart plotter, just paper charts, compass, clock, and sextant, yet unerringly delivering us to our next destination.

Seeing a more experienced crew leap into action when the valve on a gas bottle blew, blasting the gas we used for cooking into the air, anyone who knows anything about gas bottles will understand just how perilous a situation this was.

Curiously watching the skipper’s partner (I think she was a nurse) stitch up a finger he had accidentally slashed with a knife, no anaesthetic of course.

We were a completely disparate group. The only permanent crew were Ove, the skipper, his partner, and a bosun. The rest of us were itinerant crew picked up and dropped off along the way. Some of us had sailing experience, some didn’t. Yet we quickly settled into a camaraderie, sharing watches, cooking, cleaning and the myriad of tasks needed to keep an old boat like the Klaraborg in one piece. I remember dangling over the side in a harbour somewhere, hammering sisal into the gaps between the planks, which then had a caulk smoothed over the top to ensure she stayed watertight. However, we still needed to manually pump water out of the bilges regularly.

Sadly, the Klaraborg sank on July 14, 1982, off the coast of Western Australia, a few months after I flew home. The crew needed to be winched off by helicopter when the pumps failed and it started to take on water in heavy seas.

I regularly think back to those couple of months. I can still hear the wind and smell the sea. I have clear memories of the decks below, the salon filled with moments of multiple circumnavigations and adventures, the cabins, and the galley.

This was the first time I was completely outside my comfort zone, with a group of people I’d never met before, yet I needed to live on top of them for weeks in a confined space, work with them, eat with them, and make decisions with them. I discovered my youthful know-it-all arrogance was sadly misplaced; I needed to be pulled up several times, and I am grateful for the honesty and forthrightness. It smoothed some edges that needed tempering.

They talk about defining moments in your life. My time on the Klaraborg was one of those. It solidified a desire to work on the water, and I started to explore marine oceanography as a career. I even spent time on work experience at the CSIRO Marine Oceanography labs in Sydney—I wrote about my murdering work experience supervisor a few years ago! Unfortunately, that was derailed by poor showings in my school science subjects. I gravitated towards a career working backstage in theatre and music - still geeky but in a different way, I suppose.

Possibly for the first time in my life, I realised I wasn’t actually the centre of the universe, that I needed to work with others, that each of us needed to contribute, and pull our weight. At sea, out of sight of land, what you do matters. A mistake is costly.

This set me up well and explains why I so embraced working on theatre and music shows. Each show sees a group of weird, wonderful, and talented people thrown together to create something special, then after a few weeks, you each go your own way, only to reconvene in some mixture of new and old colleagues on the next show.

Backstage can be a dangerous place. I’ve seen a stagehand packed off to the hospital during a show after a pyrotechnic burnt their hand, all while the show carries on regardless. I’ve crouched way up high up the top of the flytower - the vast, tall space above the stage where scenery is winched up and down - frantically trying to lever a wire cable back into its pulley with a crowbar so the scene piece at the other end can be lowered.

Similarly, on the Klaraborg, a wind change necessitated all hands jumping onto the ropes for the sails; too much sail up when a squall hits is a significant risk to the boat and crew. Conversely, too little sail slows your speed, so it’s a constant juggle.

I’ve wondered if this love and desire for camaraderie, formed initially on the Klaraborg and later backstage, is why I moved towards founding new businesses. I know I can be impulsive, restless, and inattentive when I feel a situation is boring. I’ve had to work deliberately to suppress and manage these quirks, not always successfully. I love working on something new, an idea or a project. I commit wholeheartedly; I’ve been known to check into a hotel for two weeks and write computer code for 15 hours daily to bring an idea to life.

I do become hyper-focused on the smallest thing. I can fixate on a small object and feel a need to own it. I am also a hater of junk and mess, I like order. I’ll line up cutlery and objects on the table in a restaurant. And yeah, I know, there are also sorts of spicy brain flags amongst that!

I was about to write that I am a loner, but this is untrue. I feed off working with a great group of people, I like being social, interacting with a bunch of people, and striving towards a common goal. Yet I have a social battery that needs monitoring, I need my alone time, away from others, to allow my battery to recharge.

The personal characteristics I see in myself also make me marvel at people who remain in the same job for decades. I struggle to understand how some people’s psyche is best suited to a nine-to-five existence for years. Clearly, they have a different impetus and balance in their lives.

I’m in the midst of another sliding door moment; I recently finished full-time work at the technology company I co-founded. Let’s call it semi-retirement. I’ve moved from a diary resembling a homicide scene to one almost bereft of appointments. My new challenge is creating a structure and pattern in my days without the demands of a job. I’m still working through all that; I suspect I have some time before I properly decompress and become comfortable with a new life cadence.

I am certain that I’ll seek out the same opportunities that Klaraborg afforded me all those years ago, and then later, theatre work and technology startups. I want challenging, impactful, cooperative work, and a deep connection with a small group of other people committed to the project or cause. It’s essential to me not just to drift, but rather to have purpose in whatever I do next, otherwise I really will be all at sea,