Second Look: The Loneliness of an Intercontinental Childhood

I’m looking back at articles I wrote years ago on Substack to see how I feel retrospectively. This time it’s "The Loneliness of an Intercontinental Childhood", published in February 2021.

Writing about my peripatetic schooling was a big deal four years ago in my article “The Loneliness of an Intercontinental Childhood”. I was starting on a journey to understand my loneliness. A few weeks earlier, I’d published my first and only article on Elephant, "I’m 54 Years Old and Been Lonely My Whole Life." I received quite a few comments and Facebook friend requests, and many of the commenters told me that they shared my feelings.

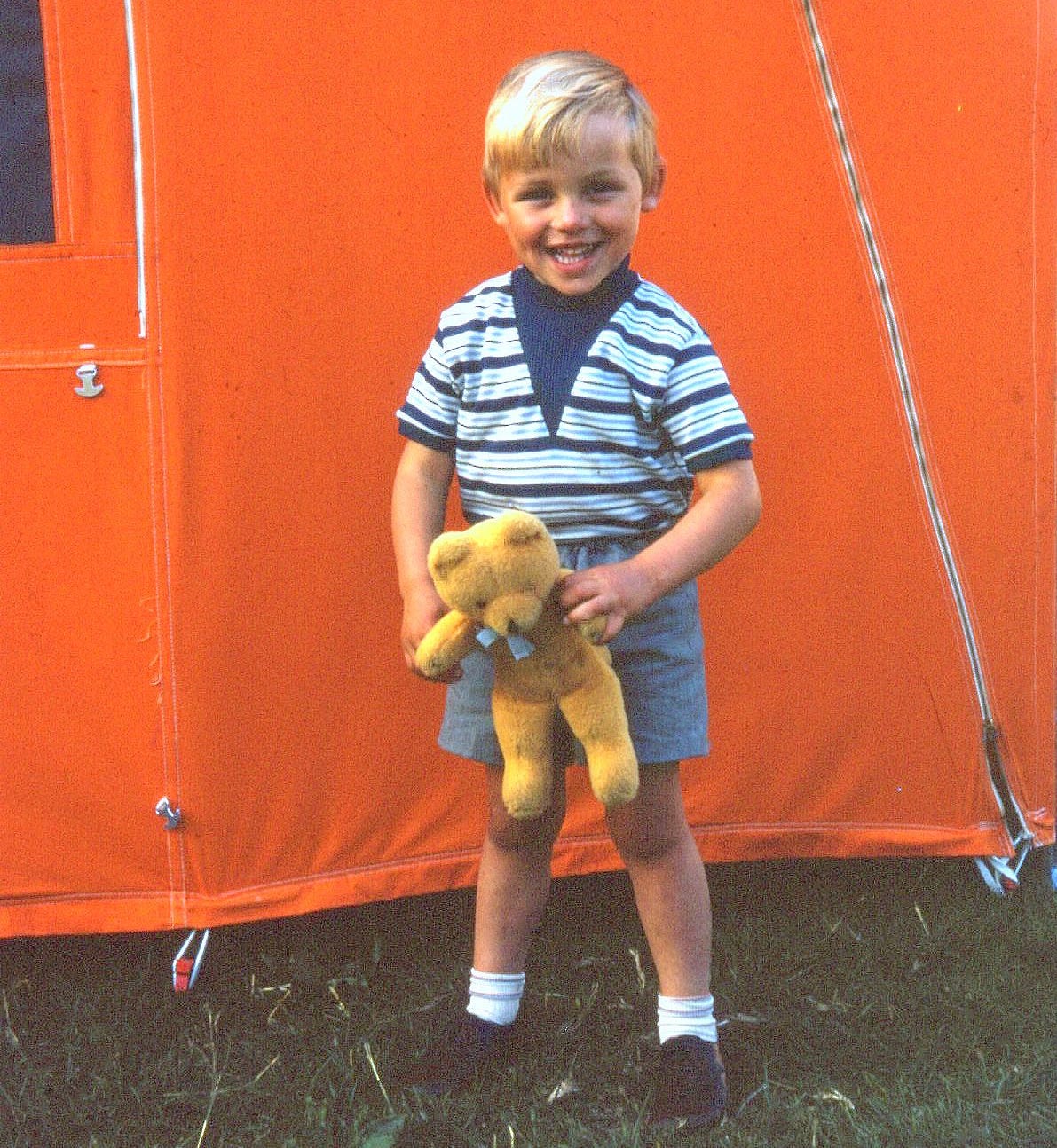

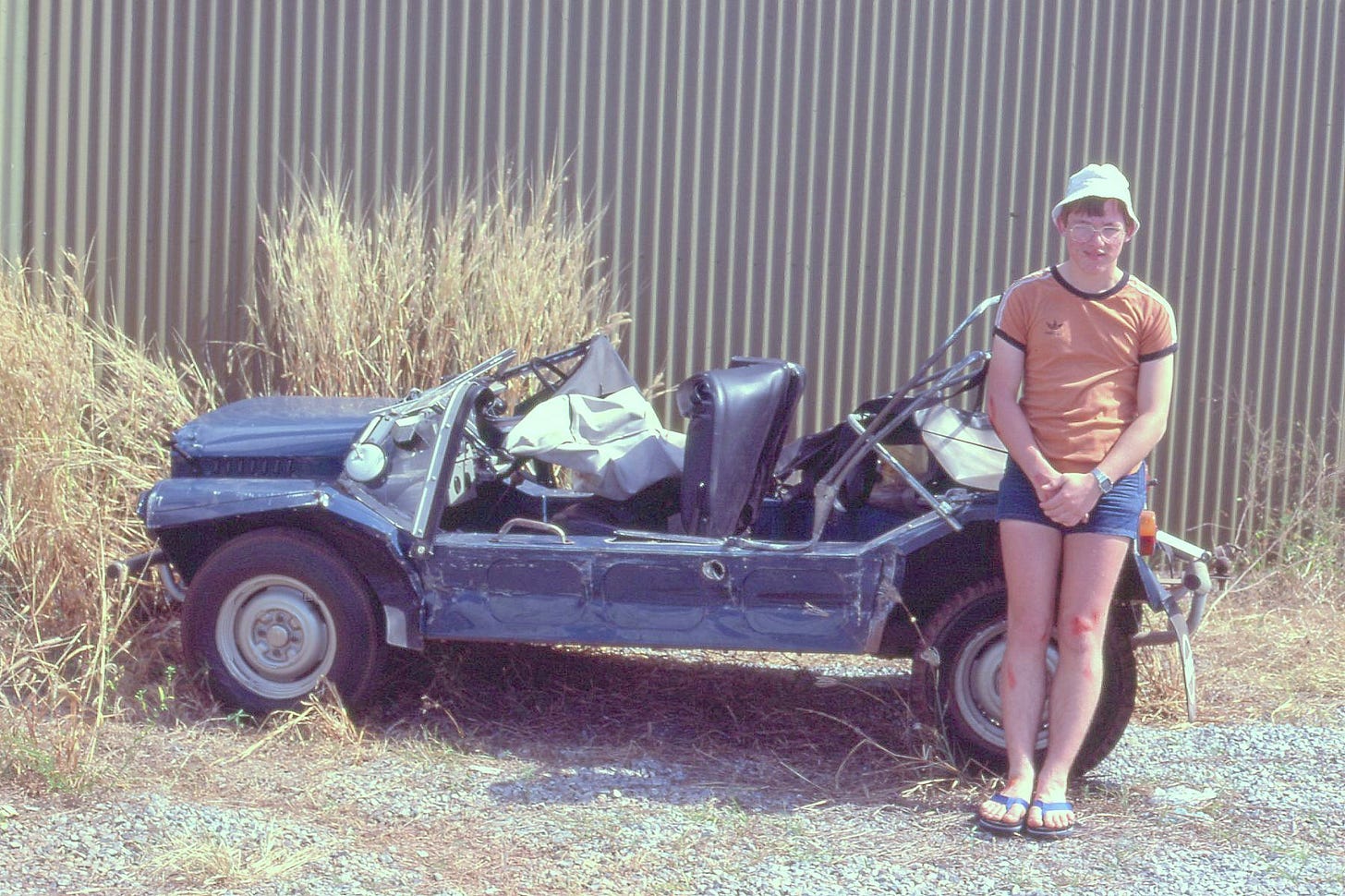

I believed I could trace my loneliness back to the day we boarded a flight to Australia in 1975, moving from the sinecure of middle-class life in the Surrey commuter belt in England to the tropical wild west of Darwin in Australia. I was nine years old and knew nothing of the world beyond my little bubble of our house in the culdesac and all the usual trappings of a young life - riding my bike, swimming lessons, school, and the long summer holidays crammed in our caravan camped on a farmers field somewhere southern like Devon.

Mum recently told me that the neighbours in our street looked down on us somewhat because we had the caravan parked at the side of the house - some considered this very ‘common’. Presumably, genuine middle-class people jetted off to Marbella or some other sunkissed destination.

Those neighbours probably didn’t realise Mum and Dad were raised working class in Liverpool, the first in their families to go to university, and who made the momentous decision when they married in the 1950s to move to West Africa to work for the British government, rather than trying to subsist in a war-ravaged England. I suspect Mum and Dad railed somewhat against the implicit class distinctions those ‘fancy’ neighbours sought to exemplify. Maybe that’s part of why they were attracted to Australia, a society way less driven by class and which university you graduated from.

Of course, the mid-70s were decades before the internet; I don’t recall reading a newspaper. Answering the (landline) telephone was a privilege you earned. It wasn’t even in our vocabulary to ring a friend up. We probably watched the television news, although my only TV memory from the early 70s was hiding behind the couch when the monsters appeared on Dr Who. My earliest music memory is our older brother playing the Dark Side of the Moon album loudly in the lounge—I’ve been a lifelong Floyd fan ever since.

Moving to Darwin triggered years of constant movements between schools.

The consequence was a perennial feeling of not belonging. At school in Darwin, I was the white pommy kid, chewed by mosquitoes. At English boarding school, I was the antipodean curiosity who was really good at swimming - we’d swum competitively with a local club in Darwin for a couple of years.

That’s why, as I reflected in my article, I was so glad my children attended only a couple of schools each. Consequently, in their twenties, their social circles include kids who were in the same school classes right back at the beginning of their schooling.

Reflecting on the article, I realise this constant transition has influenced me in several ways. I’m not sure I ever really truly feel settled. I’ve never been a homebody; a house is where I keep my stuff and sleep, but I don’t particularly worry about it being a ‘home’. I like to be comfortable - I live in Melbourne, after all, where, the other day, we ranged from 11 degrees to 31 degrees in a single day, so comfort, like air conditioning, is important. I like a good kitchen because I enjoy cooking. But I don’t spend my days leafing through Home Beautiful agonising over which throw cushions to buy next.

Until a few years ago (and after a lot of therapy), I didn’t think I even worried about not having real friends. I’ve always been self-sufficient and happy to tackle challenges alone, which persists to a degree despite much personal growth and reflection. When I moved house last year, I managed the whole thing myself—and more than one friend asked why I hadn’t reached out for help. But it's a challenging trait to break when you have a lifetime of going it alone.

The impact on students of moving schools varies, including problems developing peer relationships, and most especially, like me, an inability to maintain relationships and friendships from previous schools.

Since writing the article, I’ve pondered my friendship deficit greatly. Just the act of writing the words was highly cathartic. I’d never delved into my lack of strong, long-lasting connections and never even recognised that this was pretty abnormal.

I’ve always ‘known’ many people. I’ve worked in jobs that required interaction with many people. Working backstage in the 1980s and 90s required spending long hours near tightly knit groups of people, but none of those connections lasted or formed more deeply to persist.

Seven schools—two boarding schools—one in England and one in Australia—on two continents. No more than a couple of years at each school. In retrospect, this is not a fabulous basis for lasting friendships. And I’m not sure I was equipped emotionally. I don’t think I had the language of friendship or the tools to connect. I’m not sure why. Nature or nurture? Is my brain wired a certain way? Or should I have expected to be shown the way? I’m not sure I’ll ever know.

Recently, I read about military families who move constantly as parents are posted to a new base.

“On average, military children move and change schools 6–9 times from the start of kindergarten to high school graduation….these military children move three times more often than their civilian peers, relocating every 1–4 years” [Revolving Doors: The Impact of Multiple School Transitions on Military Children]

Research has shown that these kids face a range of challenges, including switching between curricula, adapting to new school environments and making friends, limited access to extracurricular activities, and a lack of understanding on the part of the educators in each new school of the needs of these kids - especially the context of the stressors present in military families, given their unique circumstances.

I don’t recall an educator sitting me down as I started at a new school and seeking to understand my background. That’s a pity. Maybe there were conversations with my parents that I wasn’t privy to? It is entirely possible, given the era in which I was educated.

However, I do not doubt that I endured ‘Expat Child Syndrome’:

“Expat child syndrome manifests itself in many different ways and may impact some children more than others. Common symptoms include seclusion, loneliness, withdrawn behavior and uncooperative or even disruptive behavior. In the majority of the cases children will eventually settle down and will begin to understand some of the benefits of their move abroad.”

I understand the benefits I’ve enjoyed growing up in Australia. I’m a proud Australian while acknowledging my roots, which is hard to avoid given that, despite my 50 years here, everyone around me still thinks I have an English-ish accent.

I’m not one to prosecute the past. All I do is seek to understand myself today, and reviewing and diagnosing elements of my history is essential to this process.

So I’m maybe I’m glad Mum led us kids onto the Qantas jumbo headed to Australia on Christmas Eve 1975.

David

I’m reading your article while flying from Thursday Island in the Torres Strait aboard a medium sized plane with propellers.

I’m glad to find that my iPhone has automatically downloaded your article for me to read in the air.

Moving from school to school does have its benefits. Maintaining friendships over years and developing resilience in meeting new people are good skills to have in life.

I went to three primary schools and two high schools. Not as many as you but enough to give me a varied experience. No siblings to join me in the ride.

I managed to make a few friends at every new school and have kept them all my life. One thing you can’t get more of is old friends. It’s worth investing deeply in the ones you have. They know you best and love you most.

I’m in my way home from the local hospital after being transferred from my ship at sea with kidney stones.

The ship was met by a smaller, faster boat that could race me into the hospital quicker. I was happy to see it was old friends I hadn’t seen in years manning the boat to ferry me in.

In the hospital I was looked after by the most attentive nurses and doctors. The sort of care you can only find in small places.

All of the other patients I saw were Islanders. Gentle, kind people. When I arrived one saw my uniform and knew where I was from. He said he knew my friends and which island he was from. I felt safe.

I had the agony of the kidney stones hit and was given morphine. One of the other men in the room was gently playing guitar and singing ‘Wish You Were Here’. I drifted off into the arms of Morpheus.

Thanks for your writing. It’s I wonderful thing to connect and know the experiences we’ve had growing up shape the people we become and make us beautiful patchworks of experiences.