Zen and the Art of Not Getting Mad While Driving (Through Life)

I now choose calm over chaos, acceptance over anger, understanding over irritation. Never forget, everyone on the plane arrives at the same time.

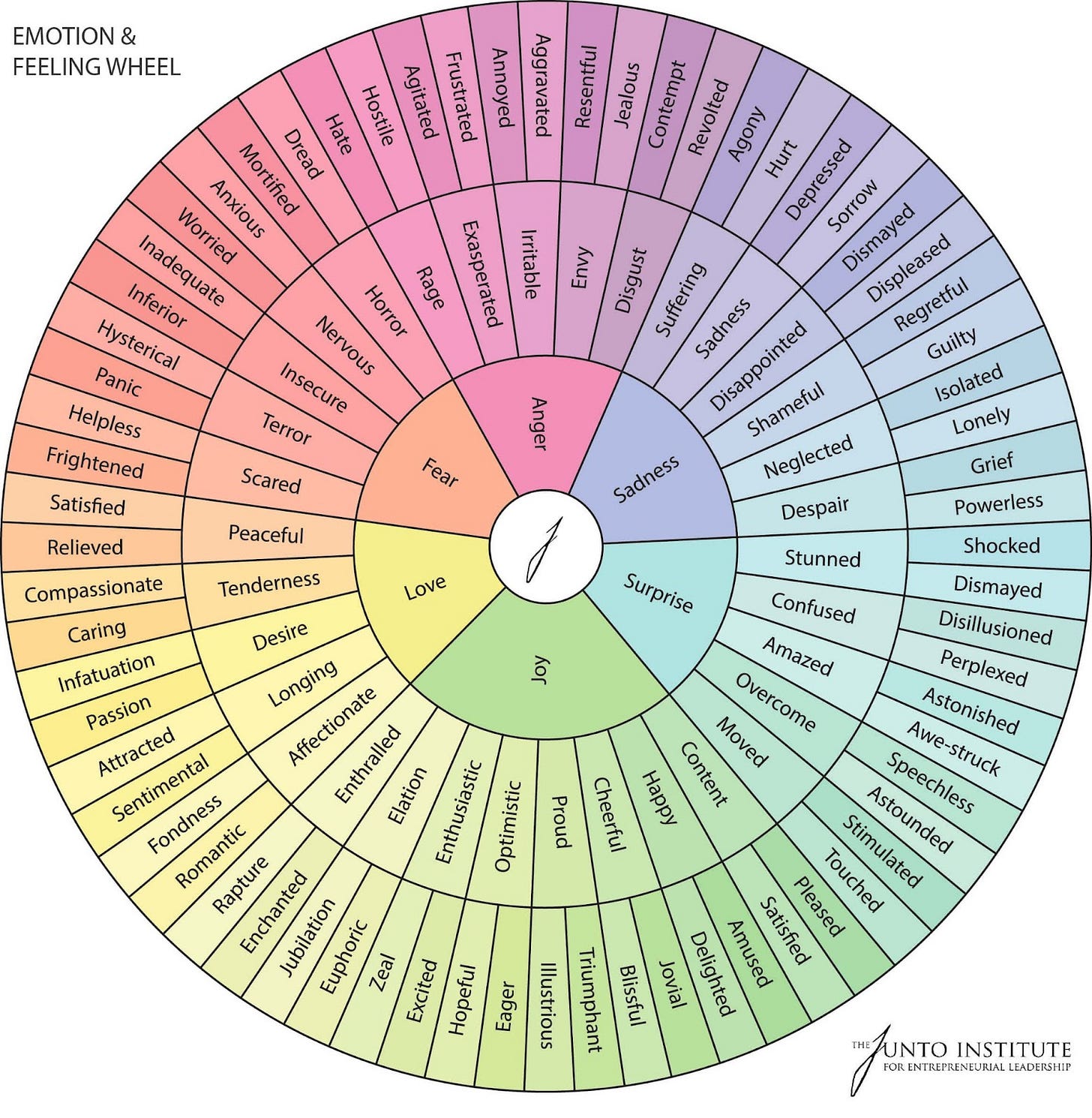

I’ve become a great deal calmer in recent years, and therapy has been crucial to recognising and understanding my emotions. A few years ago, my therapist introduced me to an emotion wheel. Each week, I'd print out the wheel and jot down little notes next to how I was feeling, aligned with the appropriate spot on the wheel. At our weekly sessions, she and I'd then discuss what triggered me to write each note, and we’d explore the connected emotion.

Feelings, Actually

This process has been invaluable in guiding the way I process emotion today. Those therapy sessions were the first time in more than 50 years on this planet that anyone actually sat me down, asked ‘how are you feeling’, listened attentively and genuinely delved into each of my responses. I cannot recommend this process highly enough.

Today I’ve learnt to take a step back in my head, examine a strong emotion - and sometimes lack of one - and consider what has triggered the feeling, or the events that led to that moment in my head. I don't have all the answers to regulating my emotions, but I know I’m calmer and more thoughtful. I’m more attentive to the feelings of others, I deliberately ask people ‘how are you?’, and endeavour to be actively listening to their responses. I wrote about being heard and understood in April:

“When we feel deeply heard, we feel less alone. When we deeply hear others, we connect in ways that transcend the superficial.

Listening is a skill to be practised and a capacity that can grow as we grow. As we accumulate our own experiences of joy and sorrow, success and failure, love and loss, we become better equipped to understand the experiences of others.”

Whilst my emotional regulation has advanced in leaps and bounds, I still have a recurring habit of replaying interactions in my head over the most minor issues, and I know I am not alone. If you've ever found yourself composing elaborate revenge fantasies about people who recline their seats the moment the seatbelt sign goes off, or plotting the downfall of parents who let their children treat the supermarket as their personal playground, congratulations: you're like me, completely and understandably human.

These days, few everyday events trigger a negative emotion in me, and I tend towards the ‘it is what it is’ philosophy.

We all have to deal with these everyday happenings. I’ve dealt with one of my young kids having a meltdown, rolling around on the floor screaming near the supermarket checkouts. I’m guessing most parents have been in similar situations. That experience means that I don’t get upset when others’ children are having a tantrum, I’ve been there. If you react, then it’s saying more about your emotions than the child or their parent. Remember, the parent whose child is having a meltdown near the checkout isn't deliberately trying to ruin your afternoon. They're just dealing with their own small human who's reached their limit. Your irritation says something about your expectations, your stress levels, and your capacity for tolerance in that moment.

Road Rage & Reclining Seats

Anyone who’s flown on an aeroplane will have a story. I’m an extremely frequent flyer and I’ve seen most of the possible poor behaviour. Feet on seats. Check. The drunk booted from the plane (from business class, no less!) before takeoff. Check. The baby who screams for an entire two-hour flight. Check. The person with no fewer than three carry-on items, one of which won’t fit in the overhead locker. Check. Bruised face because someone wears their backpack during boarding and swings without considering those already seated. Check.

There's something about being trapped in a metal tube with strangers that amplifies every minor annoyance into a major philosophical crisis. The person who reclines their seat into your lap isn't just inconsiderate. They're representative of everything wrong with modern society - so thinks my grumpy inner self.

Almost always, I am travelling alone, so I don’t have a friend or colleague to bitch to. Instead, I just have my deep breathing, headphones and Kindle to smooth over my reactions.

My calmness through the mess of flying comes from the knowledge that I cannot change anything other than how I relate to the imposts swirling around me. I can’t make the airline enforce its baggage rules. I can’t silence a yelling baby. I can try to keep my face out of the way of the gyrating backpacks. What really matters is how I relate to these realities. And that’s my emotional intelligence kicking in.

If you ask me my siblings’ mobile numbers, or even street addresses, I’d be hard pushed to tell you. It’s all in my phone on speed dial under ‘Favourites’. But I can rattle off my driver’s licence number without hesitation because I’ve written it down hundreds of times. In my home state of Victoria, kids can get their learner’s permit at 16 years old. They cannot sit their driving test until 18, and only once they have clocked up 120 hours of supervised driving with a full-licence adult in the passenger seat. I have two children with licences, which means I have spent an inordinate number of hours sitting next to them, and recording each drive in a log book, including my licence number.

I honestly am not entirely sure how driving instructors don’t lose their marbles. Especially early in their ‘learners’ hours, it can be extraordinarily terrifying to strap in and say to the young person behind the wheel, ‘ok, off we go!’. We had our fair share of near misses, although only once did we remove the wing mirror off the side of a parked car we strayed too close to.

We endeavour to teach our kids to be calm behind the wheel, to make good decisions, to leave plenty of space to the car in front, to check their mirrors and watch for all the different signage along the route.

The problem is, and I hate to confess it, driving is the one activity in which my practice of emotional regulation leaves something to be desired.

I suspect I’m becoming an increasingly irritable observer of road etiquette when it comes to criticising the cars and drivers around me. Indicators are clearly optional extras, for example. Indicators, if used at all, are turned on as a car goes around a corner, which is thus communicating useless information. I can see the car is turning. What I wanted was an ‘indication’ (the clue is in the word) in advance that the car would turn.

Some cars are driven too slowly and hold up traffic. Others go too fast, endangering everyone. Some treat freeways late at night as race tracks. Others believe it’s fine to change lanes directly in front of me, forcing me to brake and squeezing into a gap barely a car length long. Yet the same people won’t give me the courtesy of backing off a fraction to let me cross lanes. My litany of expletive-inducing driving crimes is long, and commented on by people who I have as passengers. Clearly, I have some distance to go (pun intended).

Whilst motor cars have been around for more than a century, modern life has gifted us with an entirely new category of everyday frustrations: technological ones. The Wi-Fi that drops out during important video calls, the app that crashes just as you're about to complete a task, the automated phone system that seems designed by someone who actively despises human communication.

Technology frustrations are particularly insidious because they often feel personal. Heaven save us from laptops that decide to update without permission just as you sit down to work - yet another reason I use a Mac, not Windows. When the supermarket self-checkout machine repeatedly insists that there's an "unexpected item in the bagging area" when you've followed the instructions perfectly, it feels like technological gaslighting. Even though Einstein never needed to connect a laptop to the internet, he did have thoughts about the frustrations of life in his times:

“In October 2017, Einstein’s ‘theory of happiness’ was sold at an auction in Jerusalem, for more than $1.5 million. It was a message written on a piece of hotel stationery in the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, in November 1922. Einstein wrote this as a tip for the bellboy as he supposedly had no change in his pockets at the time. He told the bellboy that it might become more valuable than a regular tip — he was so right about this. The message read:

‘A calm and modest life brings more happiness than the pursuit of success combined with constant restlessness.’”

Waiting Games

No everyday experience tests our emotional regulation skills quite like waiting. Waiting for a flight. Waiting for the doctor. Waiting on hold for an hour to talk to your bank or internet provider, although, of course, even once they answer, you will then be transferred to someone else and have to explain your query all over again.

Many companies have worked out that their time is more valuable than ours. Employing sufficient staff to answer the phones quickly costs money. Making us wait on hold costs them nothing, because they know that few of us will actually change providers, even if we threaten to do so to whichever poor sap finally picks up our call. They’ve considered the profit margin, not the people margin. Yet we consider our time is valuable, so waiting feels like a waste of time, which makes it emotionally provocative, and probably quite rightly, we get upset.

But waiting offers unique opportunities for emotional practice. Without conversation to distract you, you're forced to confront your relationship with time, control, and expectations. The person who can wait for a delayed plane without internally combusting has developed a skill that extends far beyond airline transport.

When I’m standing in a queue to board a flight, if people start jostling, I tend to remark how we’ll all arrive at the destination at the same time. Not that they listen to me. The practice here isn't about becoming passive or accepting poor service or a slow boarding of a full flight. It's about distinguishing between things you can influence and things you can't, and directing your emotional energy accordingly. You can't make the plane run on time, but you can choose whether to spend your waiting time stressed or not. Honestly acknowledging when we're being unreasonable at events out of our control, we can redirect ourselves to more useful emotional responses.

This is not about becoming emotionally numb to life's daily irritations. It's to develop what psychologists call emotional flexibility. This means experiencing frustration without being controlled by it, acknowledging annoyance without letting it dictate your actions, and maintaining perspective when small things threaten to derail your equanimity. I was reading about emotional flexibility and found this great description from London psychotherapist Selda Koydemir:

“Emotional flexibility is being connected with our emotions and moving through them. It’s about being aware of our emotions in the present moment without being defensive, but being more open and accepting of emotional experiences and, depending on the situational demands, modifying our behaviour to pursue our values and goals. Emotional flexibility brings better emotional wellbeing outcomes and allows us to pursue a rich and meaningful life. Rather than making us pursue pleasant emotions only such as happiness, it allows us to live the richness of emotions and our deepest values even in the face of difficulties. We can achieve wellbeing even when our experiences are sometimes painful. We can have any number of thoughts or emotions and still manage to act in a way that serves how we want to live.”

We carry forward so much of this from our younger years. Our responses to everyday frustrations often echo the emotional scripts we learned in childhood. If we hear Mum or Dad banging on about the poor behaviour of other drivers, we’re more likely to ape this once we are old enough to be behind the wheel. Many of our strongest reactions to everyday annoyances aren't actually about the present moment at all. They're echoes of much earlier experiences when we were learning how to navigate a world that didn't always cooperate with our needs.

The research on emotional development shows that between ages two and five, we acquire foundational skills for recognising and managing emotions primarily through watching how the adults around us handle frustration, disappointment, and social challenges.

If you grew up in a household where traffic jams led to explosive arguments, you might find yourself unconsciously recreating that intensity when faced with long queues. If your parents modelled patient problem-solving when plans went awry, you're more likely to approach disruptions with curiosity rather than rage. The beautiful thing about recognising these inherited patterns is that awareness creates choice; you can choose responses that serve you better than the ones you learned by osmosis.

The teenage years represent a crucial refinement period where we learn to navigate complex emotional landscapes. If you spent those years in environments that encouraged emotional flexibility and problem-solving, you likely developed stronger regulation skills. If your adolescence was marked by chaos or emotional suppression, you might find everyday frustrations particularly triggering. I fall into the latter. I came late to emotional enlightenment and regulation.

Is there such a thing as emotional cruise control? I’ve had years where I have flown 50 times. I have spent untold hours in airports, waiting to board a plane, waiting for the plane to take off. Waiting to disembark when the plane has landed. I’m very well practised at staying cool, calm and collected, no matter the chaos and noise around me. Sometimes I deliberately practice curiosity; I watch others, wonder what brings them to the airport this day, and ponder where they are going. I notice poor behaviour and reflect on what I can learn from the situation. Perhaps my cruise control needs a minor adjustment to maintain my inner calm. I practice acceptance. I have, mostly, and apparently apart from driving, learnt to navigate a world that doesn’t always cooperate with my needs and wants.

The greatest thing about developing emotional regulation through everyday experiences is that it transforms ordinary moments into opportunities for growth. That slow queue at the bank becomes a chance to practice patience. The crying child on your flight becomes an opportunity to develop compassion. The crashed website becomes practice for accepting technological imperfection.

Understanding the developmental roots of our emotional patterns opens up new possibilities for managing everyday frustrations. These techniques work particularly well because they address both the immediate trigger and the underlying patterns formed in childhood. I’ve found this realisation transformational - developing emotional maturity and flexibility supports me in whatever my life presents.

I don’t think there is a destination, instead a constantly iterating progress, building emotional muscles that I lacked in my younger years, rerouting emotional responses down different paths. I’m not trying to change others. That’s their responsibility. And, let’s face it, no amount of lone voice yelling and screaming at the world will effect meaningful change to the frustrations of the world.

I now choose calm over chaos, acceptance over anger, understanding over irritation. Those usually mundane moments of irritation that might have sapped my energy and well-being in the past are now mostly just vignettes to be viewed dispassionately. Never forget, everyone on the plane arrives at the same time.