Life Beyond the Facial Hair

We need to challenge some of the ingrained masculinity norms that equate vulnerability with weakness.

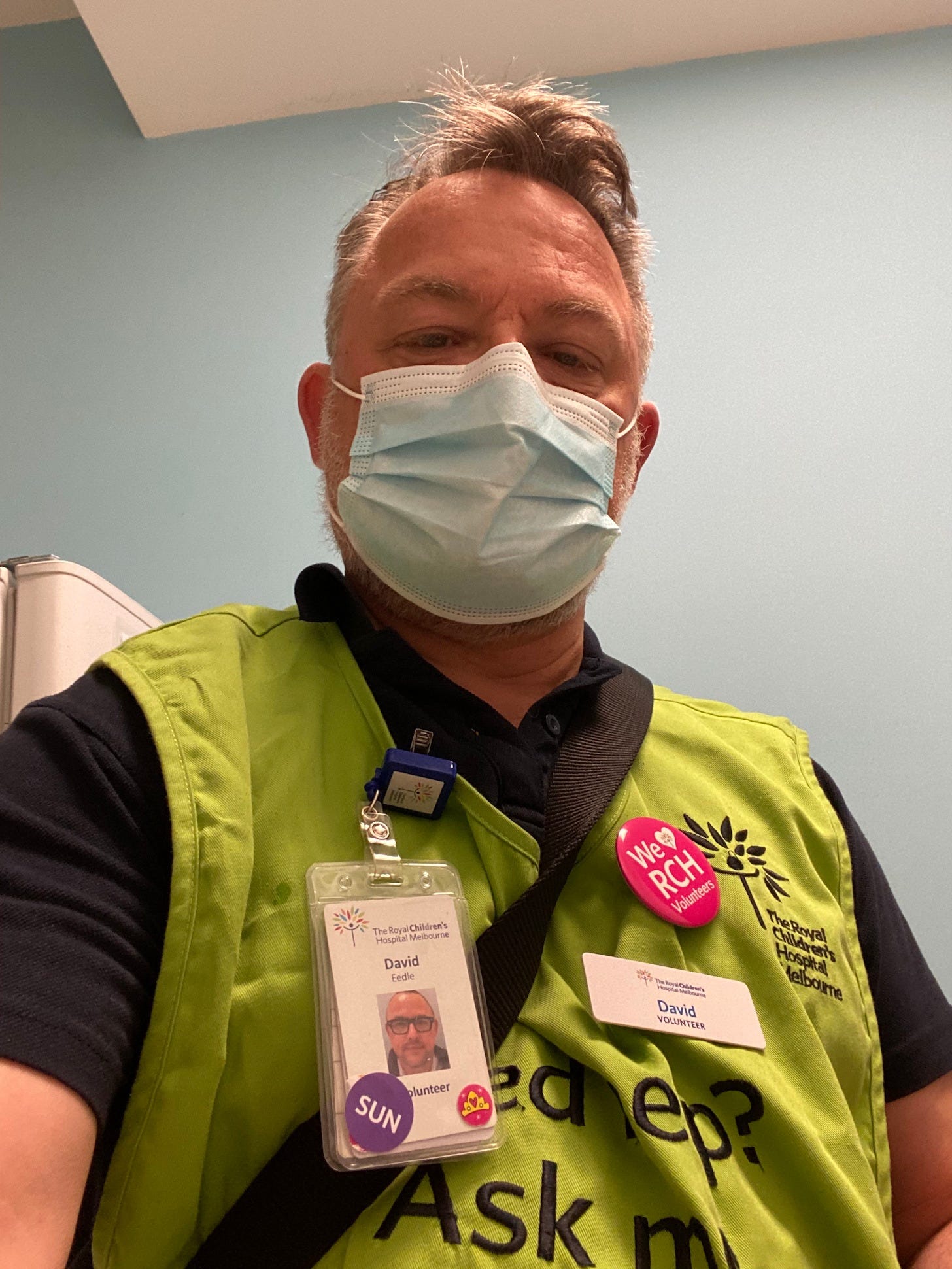

A few years ago, I had to give up a long-time volunteer job that I really valued, all because of my beard. In 2022, after almost ten years, I relinquished my role as a Family Support Volunteer in the Emergency Department at the Royal Children’s Hospital here in Melbourne. Working with children, caregivers and staff in ED was immensely rewarding, and I thoroughly enjoyed my time as part of the volunteer team.

When COVID arrived in 2020, the volunteer program was initially suspended. Still, after a few months, some of us were asked to come back in, especially to help in a newly created COVID-19 testing area and program. This was located in the multistory hospital carpark - indeed, there was both an indoor test area that had been quickly built in the carpark, and the option to drive through and be tested in your car.

In the depths of Melbourne’s winter, the nursing team and volunteers needed to rug up against the cold wind whistling through the concrete structure. After a while, large diesel heaters arrived, although you had to be careful not to stand too close in case your plastic PPE gown melted!

Later, as the world and the hospital began to settle into a new way of life with COVID still swirling through the community, volunteers started back again in the emergency department, albeit in the ‘cold’ areas - those designated for patients not with, or suspected of, COVID (that was the ‘hot’ area).

We worked in N95 masks and other PPE, although with only short shifts of a few hours once a week, we endured nothing like the stress of the medical team’s long, difficult shifts. Still, it felt enormously rewarding to be contributing in some small way.

In 2022, masks remained mandatory for everyone at the hospital, whether you were a staff member, a patient, or a visitor. And one day, volunteers received an email advising that we all needed to come in for a new mask-fitting test. Accompanying the email was a ‘beard chart’, a page with diagrams of maybe 30 different beard shapes and types with ticks and crosses to designate which were allowed or not. My problem? I have a beard, albeit I keep it very short, but the shape was not allowed, so I wasn’t even permitted to try for a fit test.

My choice was to shave my beard so I could do one four-hour shift a fortnight, or ask to be taken off the volunteer list. After some reflection, I opted for the latter. I decided I had played my part for ten years; I’d been one of the first volunteers back at the hospital when COVID struck, including plenty of shifts in the freezing car park, and perhaps it was time for others to take over. Of course, masks are no longer required today.

I tell this story for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, a key reason I felt fulfilled as a volunteer was the time spent with others during my shifts; it softened my underlying loneliness and gave me a sense of connection to a vast diaspora.

Secondly, and on reflection, interestingly, I wasn’t willing, at least at the time, to sacrifice my beard for those few hours of connection each fortnight.

Every November, a familiar ritual unfolds across Australia. Blokes start growing moustaches. Office workers host fundraising events. Social media is filled with progress photos of patchy facial hair.

All because it’s Movember:

“Men’s health is in crisis. Men are dying on average 4.5 years earlier than women, and for largely preventable reasons.

A growing number of men – around 10.8M globally – are facing life with a prostate cancer diagnosis. Globally, testicular cancer is the most common cancer among young men. And across the world, one man dies by suicide every minute of every day, with males accounting for 69% of all suicides.

Movember is uniquely placed to address this crisis on a global scale. We fund groundbreaking projects all over the world, engaging men where they are to understand what works best and accelerate change.”

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Suicide Prevention Australia:

An average of six Australian men die by suicide every single day

Males accounted for 75.3% of deaths by suicide

The Australian Institute of Family Studies has delved into the mental health of Australian men and found:

“Mental ill-health remains high among Australian men, with up to 25% experiencing a diagnosed mental health disorder in their lifetime, and 15% experiencing a disorder in a 12-month period.

Only a quarter of men said they would be likely or very likely to seek help from a mental health professional if they experienced an emotional or personal problem. Almost 25% said they would not seek help from anyone. ”

Movember is now a global movement that’s tackling issues like men’s mental health and investing in programs to counter them.

In 2020, 3,139 Australians died by suicide. Of those, 75.3% were men. That’s 2,419 men who felt their pain was unbearable and their options limited. The median age at death is 45.8 years. Middle-aged. When many of us are supposed to be at our professional peak.

Male suicides are less likely to be linked to diagnosed mental illness than situational factors. Relationship breakdown. Work stress. Financial pressure. Life transitions.

As I’ve written before about the friendship recession, men’s social circles have contracted dramatically. In 1990, 55% of Australian men reported having six or more close friends. By 2021, that figure had been cut in half to 27%. The percentage reporting no close friends quintupled from 3% to 15%. Young men under 30 are hit hardest, with 28% reporting no close social connections.

Traditional masculinity creates a double bind.

Adhering to traditional masculine norms increases psychological distress. The pressure to be strong, stoic, self-reliant, and in control takes a toll. Those same norms decrease readiness to seek help. Because asking for help means admitting vulnerability, which we’re taught is unacceptable.

The “toughness” dimension of masculinity has the most damaging effect on help-seeking behaviour. This effect is most significant among men with the most severe depression. Those who need help most urgently are least likely to ask for it.

These patterns affect men differently depending on their experiences. Research shows that gay and bisexual men often face additional layers of isolation, navigating both traditional masculinity norms and heteronormative expectations. Men from culturally diverse backgrounds may face conflicting messages about emotional expression based on both their cultural heritage and Australian masculine ideals. Men with disabilities confront assumptions about both masculinity and independence that can compound isolation.

There’s another pattern worth examining. Many men in heterosexual relationships derive fulfilment of intimacy needs exclusively from their romantic partner. We put all our emotional eggs in one basket.

Meanwhile, people of all genders who maintain diverse relationship structures often report broader networks of emotional support. For example, a 20-year longitudinal study on polyamorous families by Dr Elisabeth Sheff found:

“My study participants mentioned this as one of the primary benefits of being polyamorous: being able to get more of their needs met by spreading them out among multiple people. Sometimes they were lovers, or sometimes friends, family members, and ex-partners. The important thing is not the sexual connection, but the ability to seek and establish mutually supportive relationships beyond your partner.

Expecting one person to meet all of your needs—companionship, support, co-parent, best friend, lover, therapist, housekeeper, paycheck, whatever—puts a tremendous amount of pressure on that relationship.

In their quest to maintain sexual and emotional fidelity, some monogamous relationships prioritize the couple ahead of other social connections. When this focus reduces other sources of support, it can lead to isolation—and the resulting demands can be too much for many relationships to bear.”

Whether you’re in a monogamous partnership, practising ethical non-monogamy, or choosing solo life, the principle remains: relying on one person for all emotional needs creates vulnerability.

Australian research analysing nearly two decades of data from over 12,000 men found that those who believed they should be the primary breadwinner—particularly middle-aged men—experienced higher rates of loneliness than men without this belief, suggesting that traditional gender role expectations around work can damage social connection.

Traditional relationship models and gender roles often isolate rather than connect us.

Male friendships can be just as deep as any other friendships. But they require intentionality and vulnerability to move beyond the surface.

This is something I need to work on. I have many more female friends than male, which is why I’ve looked into organisations like Men’s Table that provide opportunities for groups of men to come together socially. I’ve even hosted a couple of small lunches for men in my constellation. It’s something I need to pursue more diligently.

A struggle for me is that most male friendships are activity-based. They play sports together, work on projects, and share hobbies. These activities create natural opportunities for connection. The minor problem is that I don’t seem to really fit into those boxes in my life.

Movember asks us to change the face of men’s health. But we can’t change the face without changing what’s underneath: the silence, the isolation, the belief that we should handle everything alone.

The moustache (or beard) is a conversation starter.

But the real work that I, and so many other men, must do is build emotional literacy and authentic connections that keep us alive. We need to challenge some of the ingrained masculinity norms that equate vulnerability with weakness. Put simply, we must recognise that we men need each other, and that needing others is strength, not weakness.

As I’ve written about the myth of self-sufficiency, we’re not meant to go it alone. Interdependence isn’t weakness. We must grow our capacity for connection. Whilst checking in on our mates is incredibly important, we must not stop there; we must cultivate friendships where other men feel safe checking in on us.

Real strength lies in connection, not isolation.

If you or someone you know needs support:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

MensLine Australia: 1300 78 99 78

QLife (LGBTQIA+ peer support): 1800 184 527

Learn more about Movember: au.movember.com